by LIBBY SLATE

THE BROADWAY MUSICAL classic West Side Story presented by an opera company? The 1940s fairy tale Brigadoon taking place in the 21st century? And a production of Come From Away where all of the actors, not just the customary onstage band members, play musical instruments?

Why not? The very nature of the performing arts is a call to creativity, and Southern California audiences will have the opportunity to experience new approaches to familiar—and one not so familiar—musicals this season.

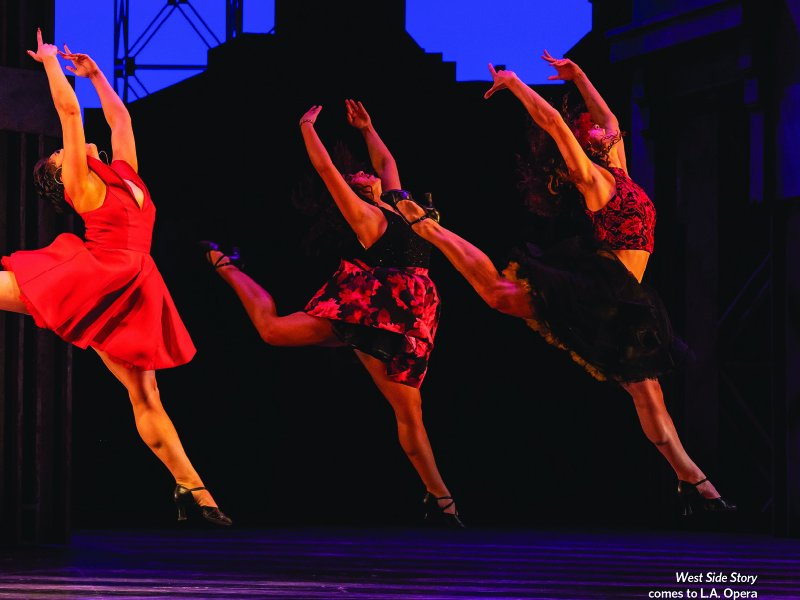

Take beloved West Side Story, which launches L.A. Opera’s 2025–’26 season Sept. 20–Oct. 12 at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion downtown.

(2) West Side Story at L.A. Opera

The Romeo-and-Juliet-inspired love story—music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim—is set amid New York City gang warfare. The work, which premiered on Broadway in 1957, won two Tony Awards and inspired two film adaptations; the 1961 original won 10 Oscars, the 2021 remake, one.

Surprise! Bernstein originally conceived the show as an opera but deemed the idea unrealistic; playwright Arthur Laurents and director-choreographer Jerome Robbins had always envisioned a musical.

“Most major opera companies in the U.S. have done or are doing West Side Story,” notes L.A. Opera music director James Conlon, who will conduct. “It took a moment in time before the imagined barriers between musicals and opera were broken down, but they are now.”

This engagement is a co-production of Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera and the Glimmerglass Festival. Washington National Opera artistic director Francesca Zambello directs the production, which stars operatic singers Gabriella Reyes and Duke Kim as Maria and Tony, respectively; the rest of the main cast is a mix of musical theater and dance performers.

Emmy-winning choreographer Joshua Bergasse reproduces Robbins’ choreography. The L.A. Opera Orchestra, numbering about 50, adds a grand-opera feel, especially as compared to ever-shrinking musical theater ensembles.

“Most people overlook the fact that the American musical is directly descended from forms of opera that alternate spoken dialogues with music,” Conlon points out. He cites German Singspiel, a musical play; operetta; French opéra comique; and the British Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas.

Though Italian composers preferred sung recitative to dialogue, Bizet’s French opera Carmen and Mozart’s German-language works did include dialogue.

“There is no reason that West Side Story, a work of undeniable genius, should not be produced on operatic stages,” Conlon says.

The conflict between the New York-born Jets gang and Puerto Rican immigrant Sharks remains all too relevant today.

Brigadoon at Pasadena Playhouse

The upcoming spring production of Brigadoon at Pasadena Playhouse is a world premiere. Its new book adaptation by actress-singer-author Alexandra Silber also emphasizes contemporary culture and sensibilities.

The basic story remains the same: Tommy and Jeff, best friends from New York traveling the Scottish Highlands, come upon the village of Brigadoon, which comes to life for one day every 100 years. Tommy falls in love with resident Fiona and must decide whether to stay or leave.

The original musical—book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, music by Frederick Loewe—opened on Broadway in 1947 and was last revived in 1980. The show’s one Tony Award, for choreography, was won by Agnes de Mille—who, prior to her Broadway career, directed at Pasadena Playhouse.

Playhouse producing artistic director Danny Feldman wanted to stage Brigadoon not just because it’s a personal favorite, but because, he says, “it’s a cornerstone American musical, one of the defining musicals when you think of the art form.

It squarely fits in with the mission of our American Musical project, which is to produce these classic musicals at grand scale. It’s not only so that audiences get to see them again, but more importantly, so that another group of people who have never seen them can experience them.”

Feldman saw “new colors” to the show with this new adaptation; it’s not just an adult fairy tale.

Silber’s book emphasizes grief and loss, fueled by her own father’s death when she was 18, and is steeped in Scottish culture. The Los Angeles native trained at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and for Brigadoon researched Scottish lore and history.

Silber also wanted to contemporize the show. “I thought, if there are things I could do to flesh out some of these stories, increase the stakes, stand inside each character, give them human richness and update them from their beautiful original prototypes—but also give them our 21st-century sensibility of what we crave from character—then this story would sing again in 2025 and next year,” she says.

The New York portions take place in the present day rather than the 1940s. As a nod to the Scottish societal matriarchy of the village’s era, one key character has been changed from a man to a woman.

Tommy and Fiona are nearing 40, with midlife questions and concerns. Jeff’s defining cynicism and excessive drinking now arise from his grief and anger at his wife’s recent death.

The village remains set in a distant time, and the Lerner-Loewe score is largely intact.

Come From Away at La Mirada Theatre

In these current turbulent times, Silber hopes audiences will leave the theater realizing “the power of love in all its forms,” and will have “the deep desire to call, write, text, connect with someone they’ve lost.”

Grief and loss could certainly propel Come From Away, the real-life story of the days following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001; 38 planes were diverted to isolated Gander, Newfoundland, and the residents suddenly had to cope with thousands of stranded passengers.

Book authors-composers-lyricists Irene Sankoff and David Hein instead focused on a more uplifting perspective, the sense of community that is created when strangers draw together.

The original opened on Broadway in 2017 and won a Tony Award for Christopher Ashley’s directing. A completely re-staged version of the show runs at the La Mirada Theatre in La Mirada Sept. 19–Oct. 12.

One major change in the new version is that, in addition to the eight-piece band of professional musicians, all 12 cast members play at least one musical instrument.

La Mirada director-choreographer Richard J. Hinds has been with the original production as associate choreographer from its 2015 beginnings at the La Jolla Playhouse, co-produced with the Seattle Repertory Theatre.

La Mirada Production Design, Music & Choreography

The La Mirada production design, by Nate Bertone, features large newspaper reproductions and smaller detailed images placed to envelope the actors in the world of 2001 Gander. A set-unit design based on Hinds’ idea of a children’s pop-up book moves scenes along and reveals surprise after surprise for the audience.

The show’s themes remain pertinent even for those born after 9/11, Hinds believes. “There always seems to be some event that happens, where that message of compassion and love and community, people coming together to support strangers during a time of crisis, becomes relevant,” he says. “My goal is that people will be filled with hope, and go out in the community and do good deeds for others. It’s the simplest thing.”

Hinds recalls the production’s history: when he helped to re-open the Sydney, Australia production after the COVID lockdown, the company performed the opening number at an event joined by a full orchestra.

“Hearing it played with that large orchestra, it really took on a sound that was almost cinematic,” Hinds recalls. “I thought, there could be moments that the show could swell and have a slightly richer sound. That was exciting to me.

Music is such a part of the culture there, it seemed to go hand in hand that our actors could play instruments—not as their characters, but as an extension of an emotion in the show.”

New choreography accommodates the actors’ movements while they hold their instruments.

The production design, by Nate Bertone, features large newspaper reproductions and smaller detailed images placed to envelope the actors in the world of 2001 Gander. A set-unit design based on Hinds’ idea of a children’s pop-up book moves scenes along and reveals surprise after surprise for the audience.

The show’s themes remain pertinent even for those born after 9/11, Hinds believes.

“There always seems to be some event that happens, where that message of compassion and love and community, people coming together to support strangers during a time of crisis, becomes relevant,” he says. “My goal is that people will be filled with hope, and go out in the community and do good deeds for others. “It’s the simplest thing.”

Photo credits: Photos from ARRIVED Magazine