by Libby Slate

One Saturday in April, the Broadway matinee of the musical King Kong had to be canceled after Act 1, when the equipment operating the 2,000-pound puppet that portrays the titular ape malfunctioned and couldn’t be easily fixed. As the show’s production stage manager reportedly told the audience, “We can’t do King Kong without King Kong, right?”

While most mishaps—equipment malfunctions, prop failures and performer errors among them—don’t bring performances to a halt, the nature of live performing means that things can and do go wrong. And when they do, the best approach is, as the British pre-World War II slogan says, to “keep calm and carry on.”

Stage manager Jill Gold, a veteran of more than 150 shows, most of them in Southern California, can empathize with her King Kong colleague.

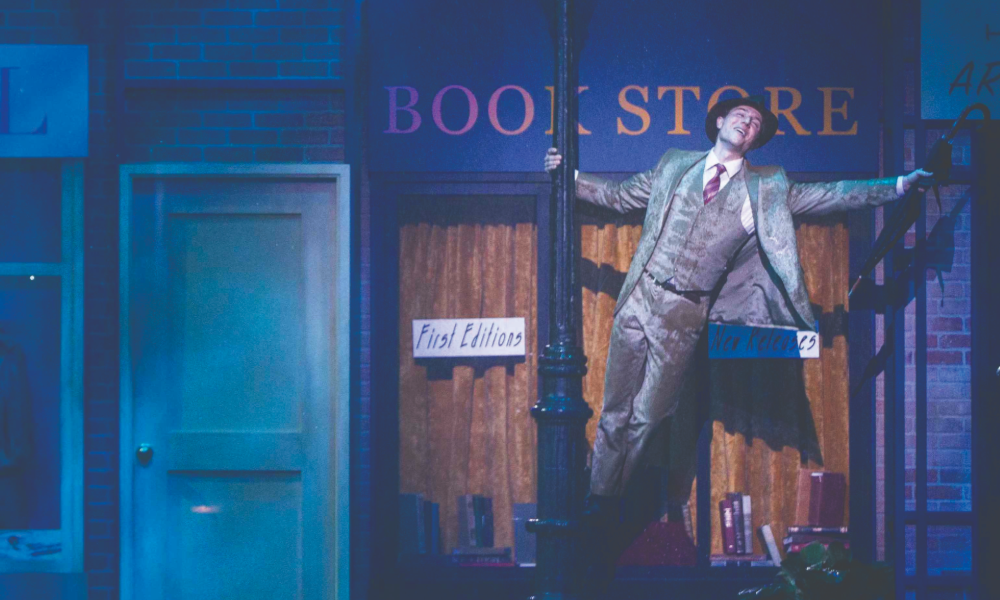

As production stage manager for La Mirada’s recent production of Singin’ in the Rain, she halted the show during a performance when the rain deck—the setting for the title song—became entangled with cables in the wings and couldn’t be moved to the stage.

“If you keep an audience sitting for more than 30 seconds, they wonder what’s going on,” she explains. “It had to take longer than that to fix, so I stopped the show.”

Gold had stopped a tour performance of Les Misérables many years earlier, when the barricade turntable got stuck—sending the actress playing Madame Thénardier flying into the orchestra pit. “I saw her disappear from the monitor,” recounts Gold, who was calling cues at the time. “The production stage manager ran to the pit to make sure she was OK. She landed on the drum kit and into the lap of the drummer! The kit had to be reassembled. She made her entrance into Paris five minutes later.”

Rupert Hemmings, now vice president of artistic planning for L.A. Opera, remembers a similar “show-must-go-on” performer mishap when he was a stage manager at Florida Grand Opera.

“In the early 2000s, the star soprano crushed her hand in a door 30 seconds before she needed to go out on stage and was swelling and bleeding like crazy,” he says. “She looked at me with wide eyes for help, and within seconds, we made a splint and bound her up with gaffer tape.

“She walked out on stage—on time —sang her aria and [nailed] it. We cleaned the wound and patched it up at the next break, and she went to the hospital after the performance. The audience never knew.”

Theater stars such as Betty Buckley in Cats, Richard Harris in Camelot and Lauren Bacall in Applause managed to avoid serious injury, or worse, when pieces of heavy equipment almost fell on or hit them.

Some performers haven’t been as fortunate: A falling steel curtain at the outdoor Muny in St. Louis almost crushed the head of late actress-dancer Ann Miller. She couldn’t walk unassisted for two years due to vertigo.

Even as ethereal an art as ballet isn’t immune to mishaps, though, says Lauren Cuthbertson, a principal with London’s Royal Ballet, “I don’t think there are that many—a fall, or a tiara gets stuck to a man’s costume.”

About the latter, she says, “there are so many jewels, you can be tangled in each other. There’s nothing you can do but yank the tiara away.”

Cuthbertson, who dances the lead in the company’s Mayerling at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion downtown (July 5-7), had her own wardrobe malfunction when the elastic drawstring on a ballet shoe slipped out. “I didn’t know how I was going to get through it, but my wonderful dresser Elizabeth, who has an aura of such calm, sewed something and worked it out.”

Performers, no matter how well rehearsed, can make mistakes. In Romeo and Juliet, there were similar settings in two scenes. In the first, Cuthbertson as Juliet danced with Romeo, and in the second, they remained apart; her partner once stayed away for the first scene.

“I do an arabesque the first time, and Romeo is supposed to be there to catch me,” Cuthbertson says. “I decided to do the arabesque, hoping it would jog his memory. It did.”

Sometimes the misadventure has nothing to do with the performance. An audience member might become ill; heavy traffic might delay a performer’s arrival at the theater.

Whatever the scenario, Gold keeps her wits about her. “You don’t want to scare the audience, and you don’t want your company to think no one’s in control,” she says.

As for those onstage, Cuthbertson says, “you have to be resourceful—and you have to keep the element of performance. The front of your head, your face, is what everyone sees. The back of your head is you thinking what you’re going to do, sorting everything out.”

Photos: Mayerling by Helen Maybanks. Singin’ In The Rain by Austin Bauman. Cuthbertson courtesy Royal Ballet.