by SHERRY STERN

Plays about distinctive immigrant experiences by three lauded playwrights come to major theaters. WHEN LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA wrote the memorable line “Immigrants: We get the job done” more than a decade ago, the lyric amused him.

He had no idea it would go on to stir Hamilton audiences performance after performance, year in and year out.

“Why does it get such a delighted response? Because it’s true,” Miranda writes in Hamilton: The Revolution.

Let’s consider these immigrants: Hair braiders transplanted from West Africa. Nicaraguan brothers striving to make a life in Miami. Young Asian women navigating a new country in the 1970s.

Their stories will play out on major Southern California stages this fall—not to mention the ongoing touring of Hamilton, about our Founding Father from Nevis, which played at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa last spring.

Each set of characters seeks their interpretation of the American Dream, making the stories both specific and universal.

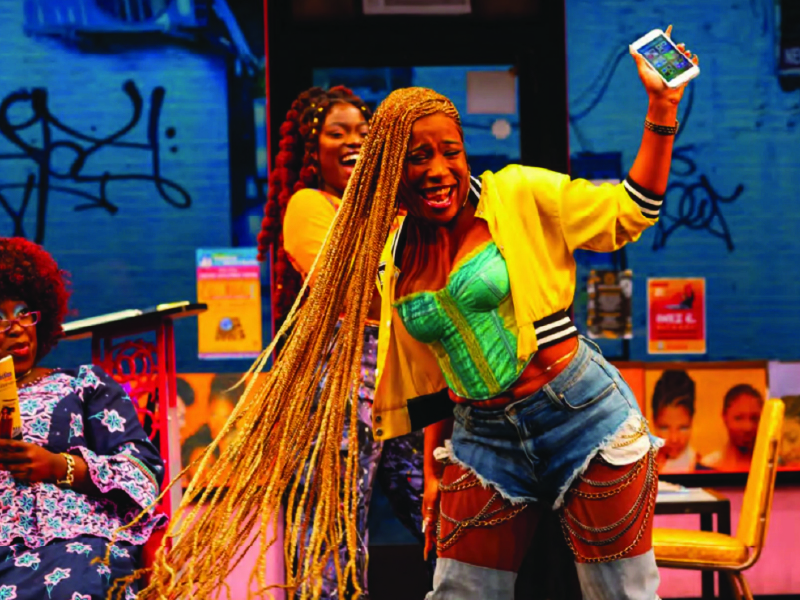

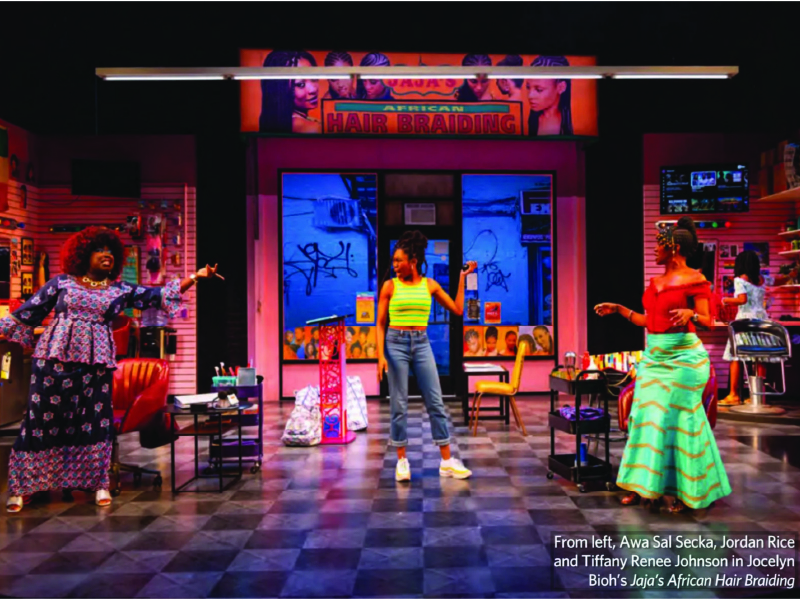

Jocelyn Bioh crafted Jaja’s African Hair Braiding, at the Mark Taper Forum through Nov. 9, about an essential community in her life: a Manhattan salon and its spirted cast of characters.

“I’ve been getting my hair braided since I was about four or five years old,” Bioh says. “So I have spent a ton of time in hair-braiding shops of all different varieties. I had a lot of stories.”

It was only natural that some of the women inhabiting Jaja’s African Hair Braiding would be immigrants. Bioh’s parents came to the United States from Ghana in 1968. “African” is right there in the shop’s name.

As she began the initial draft in 2019, deportation was a brewing flashpoint. Everyone had an opinion.

“There was a lot of conversation about immigrants and who was coming to the country, what they were doing here,” she recalls.

Being a first-generation child herself, she says, “I wanted to humanize the people behind these policies.”

What Bioh couldn’t have known was how her Tony-nominated play would hit differently as the country changed.

“When I wrote the play, we were in a different administration,” she recalls. “We were in the first leg of the current administration.

“When the play ended up on Broadway, we had a different president—and in many ways the play felt like just the teeniest bit of a relic.

Like, ‘Oh, wow, thank God we’re past that.’

“Now, a year later, the play goes on tour and the administration that existed when I wrote it is back in power. Ultimately, it has made the play feel pretty timely and timeless at the same time.”

Rudi Goblen’s new play littleboy/littleman, at Geffen Playhouse through Nov. 2, explores the lives of Nicaraguan brothers who have colliding visions of pursuing the American dream.

Says Goblen, “I wanted to explore two brothers trying to hold onto each other while growing in opposite directions—one reaching to escape, the other trying to protect what’s already here.”

As with many of Goblen’s works, littleboy/ littleman uses poetry and music, which he says are not embellishments.

“They’re the language I think in,” he says. “I come from dance, spoken word, hip-hop and ritual, where rhythm isn’t just heard but lived. Cadence, breath and lyricism shape how I build scenes, worlds and the characters that live in them.”

Goblen is a much lauded artist: a 2025 USA Fellow, Colman Domingo Award recipient, three-time winner of Kennedy Center awards, plus many other accolades.

He finds meaning in the arrival of these plays in Southern California at this time.

“Whether by design or intuition, it’s a beautiful alignment,” Goblen says.

“There is a real hunger from theatergoers, artists and institutions for stories that reflect the nuanced makeup of this country.

“Immigrant stories are American stories. They deserve to be inside any major theater.”

Yet all three playwrights set out to write plays about characters, not issues.

“These plays speak not just of arrival but of what it costs to stay. What it means to dream here. To raise children here. To feel both gratitude and grief at the same time. That will always be timely,” Goblen says.

Lloyd Suh’s The Heart Sellers, at South Coast Repertory through Nov. 16, explores Asian immigrants of the 1970s through the warm and funny interplay of two women—a Filipino and a Korean who meet by chance in a supermarket and later bond over a bottle of wine and a frozen turkey.

Suh was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for his 2023 play The Far Country.

Earlier this year, The Heart Sellers had its San Diego premiere with a different production at North Coast Repertory in Solana Beach.

While researching the 2023 play, Suh learned about the Hart-Celler Act, legislation that became a 1964 law repealing immigration quotas. For a time, Europeans were given preference over people from other countries including his characters’ Asian homelands.

Suh saw meaning in the act’s name and called his work The Heart Sellers.

“That became a powerful metaphor for the feelings I’d already been navigating,” he says.

“The women were lonely, they were scared, they were impossibly young, and they were desperately seeking moments of joy.”

The play was a bookend to an earlier work of Suh’s, The Chinese Lady, about a period in the 1880s when the United States banned the immigration of Chinese laborers. The Chance Theatre in Anaheim presented the play in spring.

The Chinese Lady and other works by Suh address issues head on.

What would become The Heart Sellers began as a conversation with a friend about their mothers; each had come to the United States in their 20s, his from Korea and hers from the Philippines.

“The impulse for this play started from character,” Suh says. “The backdrop revealed itself accidentally and surprisingly.

“During the 90 minutes that we get to spend with them, it always felt like I don’t need to think about the politics or the grander themes or how this fits into immigration. Because the women don’t want to think about that. They know it’s there. It’s part of the subtext.”

Bioh’s approach was to tell her story about a community of women with humor, a tone not usually taken on this serious topic.

“We haven’t many stories about African people and comedy being super synonymous,” she says. “Aside from one of my favorite films, Coming to America, for the most part these stories have this singular narrative of sadness and some sort of struggle or strife or disease or famine. I’m trying to add to the conversation of how the diaspora is reflected. Writing a lot about pivotal and forgotten moments in Asian American history.”

“I wrote littleboy/ littleman because I didn’t see Nicaraguan stories in American theater,” Goblen says.

“I wanted to put two Nicaraguan American brothers at the center of a story and explore things not often talked about in our communities— colorism, the pressure to assimilate, the complexities of masculinity passed down through survival.”

Goblen offers insight when asked if he might write more plays about immigrants. “While I value my immigrant background, it’s only one part of the broader tapestry I work from,” he says. “I’m a writer interested in many themes across many forms. I will continue to live in that multiplicity.”

Read the rest at: Performances Magazine Pasadena Playhouse October Issue

Photo credits: Photo courtesy of Performances Magazine Pasadena Playhouse October Issue