One day in 2003, a librarian at the Los Angeles Public Library Central Library downtown was startled to see the patron standing before him asking for assistance. It was famed cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, in town to conduct a production by Los Angeles Opera, who requested a copy of the score of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 2. The piece had been composed for Rostropovich decades earlier; the musician looked through the score, returned it and graciously accommodated the librarian’s own request, for an autograph.

The Shostakovich score is one of many in the orchestral collection of the library’s art, music and recreation department, which loans scores and parts to orchestras and other performing groups in 10 counties from San Luis Obispo to San Diego. There are about 2,400 orchestral pieces with parts, as well as other types of scores, for a total of about 300,000 pieces of music.

“The collection serves a wide audience,” says librarian Emma Roberts, an art- and rare-book specialist. Scores are checked out and performed by local orchestras, school ensembles, choral groups and opera societies. “Last year, over 182,000 people enjoyed performances using Los Angeles Public Library’s orchestrations.”

Scores are available for a $20 handling charge; rental fees elsewhere can be $600. The collection is just one element of the performing-arts treasure trove; there are also books, plays, librettos, theater programs, clippings, photos and sheet music.

“The library has been collecting in these areas since its early beginnings,” Roberts notes, “and the collection has grown in depth and breadth since then.” Its history and its accessibility make it unique.

Much of the music-related holdings are in closed—closed to the public—stacks. A tour led by Roberts and music librarian Caroline Zakarian reveals a music lover’s wonderland of floor-to-ceiling shelves of colorfully bound books. There’s also sheet music—piano solos, choral works, sacred music—in alphabetically labeled gray boxes.

There are bound concert programs galore, from the L.A. Phil and Music Center lease events, but also from the Boston Symphony Orchestra (from 1892), Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra and London’s Royal Music Association. Books include such titles as The Art of Judging Music by composer Virgil Thomson; Evenings With the Orchestra, by composer Hector Berlioz; and Essays on Music, by musicologist Alfred Einstein. As with sheet music, some works circulate and can be transferred to another branch; others are for reference only.

In Rare Books is the Behymer Collection, available by appointment only, an assemblage of photos, posters, portraits and clippings of opera singers and other performers presented in Los Angeles in the early 20th century by impresario L.E. Behymer. There are also programs, such as those for People’s Chorus concerts (1913-14) and books, among them The American Musical Miscellany: A Collection of the Newest and Most Approved Songs, Set to Music—newest, that is, as of its 1798 publication date.

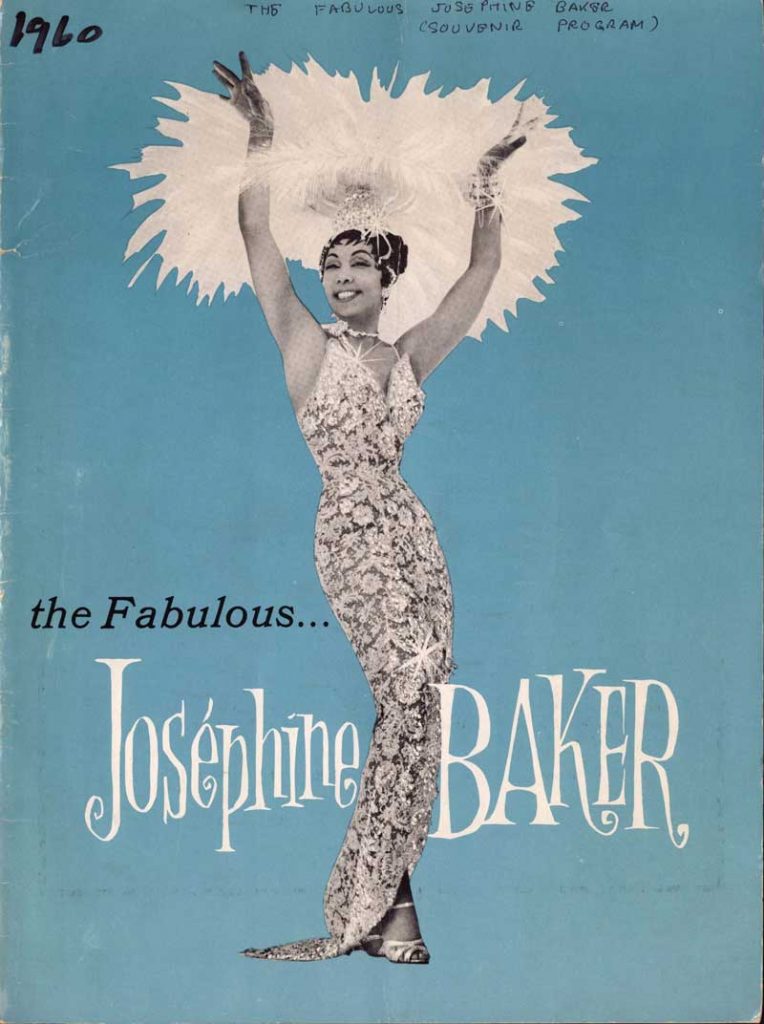

Theater lovers head to the literature and fiction department, a repository of books, theater programs, clippings, reviews and photos. The Theatre Programs and Playbills Collection boasts some 30,000 programs, going as far back as the 1880s, some from New York and London. Here’s Kate Hepburn starring in As You Like It at the Biltmore Theatre; there’s Clark Gable as a Montague servant in Romeo and Juliet in the Friday Morning Club building playhouse. An ad in the Los Angeles Amusement Journal, billed as the official program of the Grand Opera House, touts homes for sale for $20 down and $10 per month.

There are photocopies of local newspapers’ theater sections. Files donated by the Los Angeles Times contain materials used by the paper’s theater critics: production press releases, photos, even printouts of the reviews as written on the critic’s computer. The Audrey Skirball Kenis Unpublished Play Collection yields more than 800 bound scripts of plays produced locally but never published.

A wide range of patrons uses the collections, says Christa Deitrick, in charge of the theater programs. “They could be researchers, scholars, someone writing a book,” she notes. “Or it could be someone who grew up seeing shows here,

or who loves theater, and wants to see the old material.” The programs help preserve the legacy of demolished Los Angeles theaters, she adds: “This fabulous collection tangibly illustrates the grand sweep of L.A.’s theatrical past and offers scholars and fans alike access to these artifacts of our city’s rich cultural history.”

And finally, the history and genealogy department is home to some decidedly different performing-arts items: documents, photos, props and costumes of the archives of the Turnabout Theatre, a local 1941-56 revue that featured political send-ups and comic-dramatic theater performed for adults by … marionettes.

Visit lapl.org for more info.